the Biggest Challenges Facing Foreign Companies Expanding to the U.S.

The United States offers foreign companies unmatched opportunities, but success here doesn’t come easily. Expanding into the U.S. demands more than ambition—it requires navigating a vast market, adapting to cultural differences, and building a credible presence in one of the most competitive environments in the world. (Originally published in The Financial Times, November 2024)

The United States offers foreign companies unmatched opportunities, but success here doesn’t come easily. Expanding into the U.S. demands more than ambition—it requires navigating a vast market, adapting to cultural differences, and building a credible presence in one of the most competitive environments in the world.

The Challenge of Market Dynamics

The U.S. isn’t one market—it’s a collection of diverse regions, each with its own consumer preferences and behaviors. Strategies that work in one area may fall flat in another. Foreign companies often underestimate the effort required to gain trust and win over American consumers, who expect localized products and exceptional customer service.

Take Renson, a Belgian manufacturer of high-end outdoor living products. Despite their global reputation, they faced challenges aligning their offerings with U.S. market demands. To succeed, Renson adapted their approach, emphasizing partnerships with local distributors and tailoring their marketing strategies to meet regional preferences. Winning in the U.S. means understanding that one size doesn’t fit all.

Understanding American Culture

Cultural nuances can make or break a company’s U.S. expansion. Americans value individuality, direct communication, and fast decision-making—traits that can feel at odds with practices in

more hierarchical or consensus-driven cultures. Misalignments in management styles or customer engagement strategies often result in frustration and lost opportunities.

Consider Too Good To Go, the Danish food waste app. When entering the U.S., they realized that Americans’ attitudes toward sustainability were tied closely to convenience and cost. By tweaking their messaging and focusing on these priorities, they managed to resonate with their new audience and find success in a market that initially seemed overwhelming. Adapting to cultural expectations is essential for building strong connections with American consumers.

Building a Market Presence

Gaining visibility and trust in the crowded U.S. marketplace is no small feat. American consumers are brand loyal and expect businesses to prove their value quickly. Establishing partnerships, creating robust distribution networks, and investing in compelling marketing campaigns are non-negotiable.

Too Good To Go also demonstrates the importance of credibility. They worked hard to build local partnerships with businesses committed to sustainability while leveraging targeted marketing to engage consumers. This dual approach helped them gain traction in a competitive environment. Success requires persistence and a willingness to think locally.

The Bottom Line

Expanding into the U.S. is a challenge, but it’s also a transformative opportunity. To succeed, foreign companies need to be prepared to adapt—whether it’s tailoring their products, embracing cultural differences, or building strong relationships with American partners. Do that, and you’ll be well on your way to making it in America.

This article was originally published in The Financial Times, as Matthew was a speaker at this conference.

When Did The American Dream Begin?

The idiom “American Dream” became a catchphrase in 1931 when James Truslow Adams featured it in his best-selling book, The Epic of America. He wrote, “The American dream is the belief that anyone, regardless of where they were born or what class they were born into, can attain their own version of success in a society in which upward mobility is possible for everyone. The American dream is believed to be achieved through sacrifice, risk-taking, and hard work, rather than by chance.”

The idiom “American Dream” became a catchphrase in 1931 when James Truslow Adams featured it in his best-selling book, The Epic of America. He wrote, “The American dream is the belief that anyone, regardless of where they were born or what class they were born into, can attain their own version of success in a society in which upward mobility is possible for everyone. The American dream is believed to be achieved through sacrifice, risk-taking, and hard work, rather than by chance.”

At the time, the country was in an economic depression following the stock market crash of 1929. Half of U.S. banks failed, and unemployment was at 30%. Adams believed the country had forgotten its foundational principle, promised in the Declaration of Independence, that all people could achieve life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. He wrote The Epic of America to inspire people to dream once again, and he wanted to remind people that the United States was different from England and the rest of Europe, where upward mobility was limited by the family and place in society where one was born. Comically, James T. wanted to title the book The American Dream, but the publisher didn’t think people would spend $3.50 for a book about a dream.

Historian James Truslow Adams (from Boston Globe) and Unemployed men at the White Angel Breadline in San Francisco, California 1933 (Photo by Dorothea Lange)

James Truslow Adams also commented on the country’s obsession with material things, which had reached a new level during the “Roaring 1920s.” He felt that Americans were obsessed with money and mass consumerism, since many people could afford to buy automobiles and live a lavish lifestyle. Reflecting on the American Dream, he wrote: “It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of a social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.”

The essence of James T.’s vision of the American Dream was the idea that every person in the U.S. has the opportunity to achieve their personal goals. And this idea of opportunity for personal fulfillment for all citizens was documented in our Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights.

The American Dream Today

According to Gallup Research, 70% of Americans believe the American Dream is achievable. And 31% of U.S. adults report their families have achieved the American Dream, with another 36% saying they are “on their way” to achieving it.

However, there is no consensus on what the American Dream is.

The American Dream is often portrayed in our entertainment media as a sole focus on acquiring tremendous wealth and material things. After all, Madonna sang about being a “material girl.” And a long-running TV reality show was called “Who Wants to Marry a Multi-millionaire?” And let’s not forget the movie “Jerry Maguire,” in which Cuba Gooding, Jr.’s character told Jerry, played by Tom Cruise, to “Show me the money!”

Although endless material wealth is some people’s dream, that idea is more theater than reality. A truer picture is that America is a land of dreams where anything is possible—which might or might not include huge financial success. In fact, many people measure the rewards of their dreams in non-monetary terms, such as achieving freedom from their countries’ political restrictions or finding work that makes a positive impact on the world.

My American Dream Story

I’m one of the 31% of U.S. citizens who believe they have achieved and are living their American Dream. What’s more, as I recounted in this book’s Introduction, I’m also a product of the American Dream: my ancestors immigrated to the U.S. around the turn of the 20th century, seeking a better life than the one they had in Eastern Europe.

Gallup Research shows that 70% of Americans believe the American Dream is achievable. And 31% of U.S. adults report their families have achieved the American Dream, with another 36% saying they are “on their way” to achieving it, according to Pew Research.

I’m one of the 31% of U.S. citizens who believe they have achieved and are living their American Dream. What’s more, as I recounted in this book’s Introduction, I’m also a product of the American Dream: my ancestors immigrated to the U.S. around the turn of the 20th century, seeking a better life than the one they had in Eastern Europe.

But I also feel extremely grateful and lucky regarding the circumstances of my life today. I’m married to a wonderful person, live in a comfortable house, enjoy my work, and have two smart and talented children. I’ve also had some happy successes in my career. I owe much of that success to my upbringing in a supportive environment and the many opportunities handed to me, which not every American child experiences.

I grew up surrounded by books, newspapers, and magazines. My mother was a public school librarian, and she regularly brought home the latest books for my brother and me. My father read five newspapers: Boston Globe, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Christian Science Monitor, and Jewish Forward. Our family also subscribed to Newsweek, People, Sports Illustrated, and U.S. News & World Report. You could say we were “news junkies.”

As a teenager, I fulfilled an early dream of writing for a newspaper in Brookline, Massachusetts. Like many American Dreamers around the world, I’d been highly influenced from watching movies. I became attracted to journalism after viewing “All the President’s Men” — the story of two journalists, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, who uncovered the Watergate scandal that led to Richard Nixon’s resignation as President. Later, after I became an editor of the high school newspaper, The Brookline Sagamore, I achieved another dream when it won a Gold medal from Columbia University’s School of Journalism for being one of the best high school newspapers in the country.

Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford in "All the President's Men." Photography from Alamy

The Sagamore’s faculty adviser, Sandy Fowler, convinced me to study something other than journalism in college, though, believing that the best journalists become experts in a subject, such as science or music, and then find publications where they can write about it. I chose the subject of business and enrolled at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, which had both an excellent student newspaper and business school.

During college, I had a summer job at The Boston Globe newspaper. Mostly it was calling and interviewing people over the telephone. There was a close political race for governor of Massachusetts, and the Globe wanted to get a pulse on voters’ sentiment. The work also included market research for local advertisers. It was extremely boring and nothing like the glamour of Woodward and Bernstein. I never got to write and publish a single sentence.

After college, I worked in New York City with Backer & Spielvogel Advertising. The agency, which later was absorbed by Saatchi & Saatchi, produced memorable campaigns for brands such as Miller Lite, Sony, Wendy’s and Campbell’s Soup. We also introduced Hyundai into the United States. (Article on Hyundai Launch) Over the next two decades, I worked in management roles for several successful companies, including BIC, Chinet division of Huhtamaki, Digitas, Pitney Bowes, and Snapple Beverages.

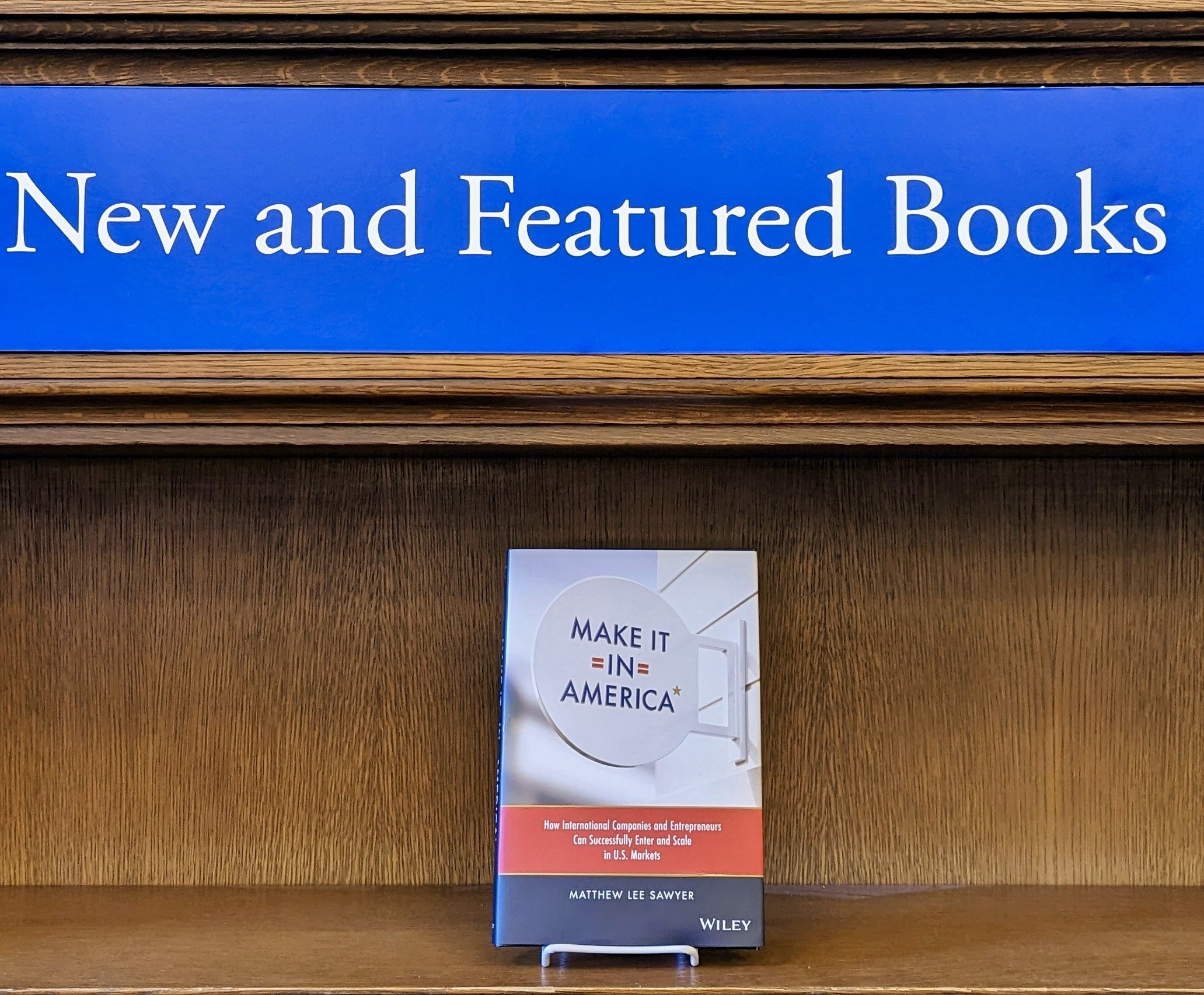

Through the years, however, I still had one major unfulfilled dream: writing and publishing a book. Then, in 2014, I stumbled happily into teaching and consulting. That work placed me on a path to writing my first book — Make It In America—and finally fulfilling an ultimate dream.